Circa AD 940 the Umayyad caliph, ʿAbd al-Raḥmān III founded Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ as the new capital of al-Andalus. Literary Arabic sources provide descriptions of its terraces, gardens, columns and marble decoration, as well as its collection of Roman sarcophagi and sculptures, which are referred to as basins (ḥiyāḍ) and “wonderful statues of human figures (tamāṯilʿaǧībat al-ašḫāṣ) that not even the imagination could explain”. Literary sources also indicate that “there was no one, absolutely no one, who entered the Alcazar [of Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ], even those from the most distant countries and diverse confessions, whether king, emissary or merchant,” who were not overwhelmed with “bedazzlement (bahr) and astonishment (raw)”. The city conveyed “the splendor of the monarchy (bahǧat al-mulk) and the majesty of power (faḫāmat al-sulṭān)”.1al-Maqqarī, Nafḥ, I, pp. 367, 392-393 and 566-567. On the foundation of Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ as a scenario of the caliph’s power and representation: Manzano, La corte, pp. 321-329.

Archaeologists have recovered fragments of the Roman sarcophagi and statues mentioned in the literary sources. Scholars have sought to explain how and why antiquities from the Ǧāhiliyya (Age of Ignorance) came to be deemed acceptable for display in the palace of an Islamic ruler and what specific aesthetic and ideological roles were assigned to Roman artworks. Scholars have identified an Umayyad “antiquarian taste,”2Beltrán, “La colección”, pp. 109-110. while, stressing that ancient sculpture “was surely ‘read’ as non-Islamic and exotic”.3Ruggles, “Mothers”, pp. 84-85. In contrast, Acién examined the issue of the Islamic re-signification of Pagan sculpture. He discussed a female statue that was viewed as a talismanic representation of Venus, and it also conveyed both a political and religious meaning.4Acién, “Materiales”, pp. 189-190. Calvo was the first scholar to study the context in which these sculptures would have been displayed. She argued that the antiquities were placed in spaces dedicated to science and learning, whereby they became “allegories” for the “science of the Ancients” and served as “a visual reference for classical antiquity”.5Calvo, “The Reuse”, p. 25.

Over the course of this study, I explore this line of inquiry, leading further previous research on the topic,6Elices, “La reutilización”, pp. 9-14, “La escultura”,112-114 and Antigüedad, pp. 345-364. but rather than seeking just a single meaning or role that was ascribed to Roman artifacts, the collection at Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ is addressed in terms of its transcultural significance. The caliphal collection was based on the use of spolia, which Kinney has defined as “any artifact incorporated into a setting culturally or chronologically different from the time of its creation”.7Kinney, “The Concept of Spolia”, p. 233. Therefore, spolia always denotes a recognizable difference (whether temporal, technical, cultural). I explore how this was a key factor that shaped perceptions of these sculptural objects difference and historical significance. By engaging with spolia, the Umayyads turned their display of antiquities at Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ into a transcultural collection, as it was neither entirely Classical nor Islamic; instead, it was miscellaneous, gathered from a wide range of origins, culturally heterogeneous or ambiguous, and intended to have a broad appeal to a diverse audience, as literary sources report. Furthermore, a key facet of this study is to demonstrate how the transcultural nature of this sculpture collection was planned and conceived by the Umayyads caliphs as a strategy for legitimizing and commemorating their rule. Thereby, the antique sculpture displayed at Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ sought to assert the diverse interwoven dimensions and universalism of the caliphs' power.

A miscellaneous collection, a planned display

⌅Two handicaps must be taken into consideration when studying the Roman sarcophagi and statues reused at Madīnat al-Zahrā. Firstly, the sculpture is in a poor state of conservation, and only fragments of the original works have survived. During the period of crisis that beset the Umayyad caliphate between 1009 and 1031, Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ was repeatedly sacked, before being abandoned at the end of the twelfth century. As a result, the sarcophagi and statues were destroyed. Both the figural and non-figural sarcophagi suffered the same fate, which suggests that these sculptures were destroyed for lime production.8Vallejo, La ciudad califal, p. 262. Secondly, the lack of archaeological context is a major handicap, as the fragments were exposed to centuries of rainfall and washed away into piles found at a range of locations. Thus, the places where fragments of sculpture have been found are not necessarily the locations where they were originally displayed. Only in a few cases, has it been possible for archaeologists to gather the fragments and reconstruct the parts of the original sculptures. Their meticulous labor revealed that most of the sarcophagi were reused as water basins.9Beltrán, “La colección”, p. 110; Vallejo, La ciudad califal, pp. 237 and 242, note 47. Pipes and other elements of plumbing were recovered during the archaeological excavations, and all the aforementioned sarcophagi have openings on their bases and sides in order to adapt them for reuse as water basins. The position of these openings has enabled researchers to identify the exact location of a number of sarcophagi, which were placed in the center of certain courtyards in Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ.10Vallejo, La ciudad califal, pp. 237, 242, note 47 and lam. 193. Making allowances for these handicaps, the extant sculpture collection is remarkable. At present it comprises thirty items, including Roman sarcophagi, both figural or non-figural, as well as basins and life-sized sculptures. No other pre-Islamic material was reused at Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ, which suggests that the criteria for the selection and reuse of antiquities focused on the sculptures’ singularity, the powerful figural narrative they conveyed, and their suitability for their new dual decorative and ideological function.

The collection is a miscellaneous one, comprising a wide range of items of different sizes and a variety of figural decoration. The craftsmanship, composition, and iconographic scenes depicted on these sculptures reveal them to be highly singular artifacts,11Beltrán, Los sarcófagos, 112-116; Vallejo, La ciudad califal, pp. 116 and 261-262. and in fact most of the figural sarcophagi are high quality pieces, made of Thassos, Parian, or Proconesian marble, which had probably been imported from Rome.12On the figural sarcophagi see: Beltrán, Los sarcófagos, pp. 32-37 and 112-166 and Beltrán, et al., Los sarcófagos, pp. 126-127, 131-141, 143-152 and 164-171. A remarkable example is the Sarcophagus of Meleager and the Calydonian boar hunt (Fig.1), which was made either in the third century or at the beginning of the fourth century A.D. However, other works have been dated to the second half of the fourth century, and even to the fifth century A.D.13Beltrán, et al., Los sarcófagos, p. 168. The dimensions of these sculptures vary considerably. For example, fragments have been found of a sarcophagus that depicted standing or seated figures holding uolumina —scrolls— and wearing cloaks. They formed part of a remarkably large piece —1’4 high, 2’ long and 1.2’ wide — which has been identified as the Sarcophagus of Philosophers and Muses.14Beltrán, et al., Los sarcófagos, p. 140.

Image by the author with permission of the Archaeological Site of Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ

Figure 1 Sarcophagus of Meleager. Reconstruction Image by the author with permission of the Archaeological Site of Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ

Regarding the free-standing sculptures, fragments of at least four different portraits have been discovered so far. They all are dated to the second and third century AD and include the remnants of a striking herma that depicted Hercules as a child. It is an ornamental piece of Numidic giallo antico marble and constitutes an exceptional piece, as this kind of antique representation of the Greek hero is rare (Fig. 2).15Beltrán, “La colección”, p. 112; Beltrán, “Hermeraclae”, pp. 163-166.

Image by the author with permission of the Archaeological Site of Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ

Figure 2 Herma of Hercules as a child Image by the author with permission of the Archaeological Site of Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ

Figural sarcophagi and statues were displayed together with non-figural sarcophagi and circular basins. The sarcophagi that were reused were made of Proconesian marble and denote a standardized size, but in contrast, the basins were made ex novo with no figural decoration at all.16Vallejo, La ciudad califal, pp. 238-240 and 262-263, note 89. The only exception is a circular dodecagonal basin that stands out for its vegetal decoration and dimensions. It is most probably a pre-Islamic vessel that was reused and located in the room adjacent to the Salon Rico (building nº 42), which is today known as “Patio de la Pila” (Fig. 3). A stone base or support was attached to the basin, which was equipped with lead pipes to supply water.17Pavón, “Influjos”, pp. 216-217; Hernández, Madinat al-Zahra, pp. 58-59; Castejón, Medina Azahara, p. 29; Vallejo, La ciudad califal, pp. 116, 240 and 262.

Image courtesy of the Archaeological Site of Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ

Figure 3 Patio de la Pila Image courtesy of the Archaeological Site of Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ

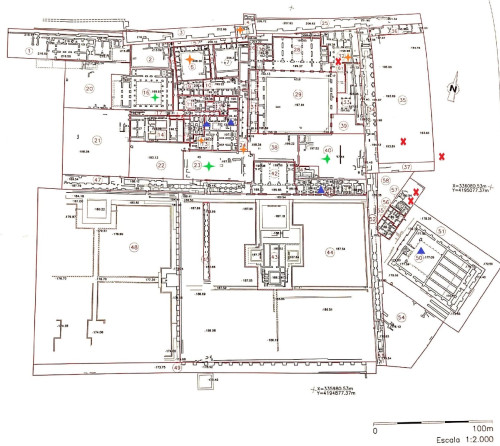

The display of sarcophagi and statues was carefully planned: they were intended to be seen and noticed, and were located in prominent public spaces. Figural sarcophagi were placed in courtyards that were used for administrative duties, or else reserved for meetings, public ceremonies, and official receptions of embassies (Fig. 4).18Calvo, “The Reuse”, pp. 17-25 associated the pieces with learning spaces. However, as Vallejo argued this was not the case for most of these sculptures, La ciudad califal, pp. 240 and 262-263. The sarcophagi also reinforced the significance of some spaces over others. The ornamented front of the Sarcophagus of Meleager faced the western portico of the Court of the Pillars, where it was displayed.19Beltrán, “La colección”, p. 110; Vallejo, La ciudad califal, pp. 237-238. In contrast non-figural sarcophagi were placed in residential areas and transitory spaces or those used for menial activities.20Vallejo, La ciudad califal, pp. 238-241. The singular dodecagonal basin mentioned above (Fig. 3) was located in the room adjacent to the Salon Rico, which was a highly significant space and it was used as a bath and embellished with marble niches.21Vallejo, La ciudad califal, pp. 242-247. The statues were displayed in public spaces, most probably in locations close to where they were retrieved by archaeologists, in the eastern sector of the palace. The herma of Hercules and a fragment of a head corresponding to a masculine portrait were found in the residential buildings near the mosque (nº 50). A bust of a male portrait was also located in a courtyard attached to building nº 28. Finally, three fragments, retrieved from two different locations in the area surrounding the Portico (nº 34), belong to a female portrait. (Fig. 5).22Beltrán, “La colección”, pp. 112-113; Vallejo, La ciudad califal, pp. 178 and 262-263. I am grateful to A. Vallejo for clarifying the location of the discovery of the sculptures. It is wrongfully mentioned in earlier publications by several scholars.

(Plan: Antonio Vallejo Triano, La ciudad califal de Madinat al-Zahrāʾ: Arqueología de su excavación [Cordoba, 2010], fig. 9 [reproduced with the author’s permission]).

Figure 4 Map of the excavated sections of the Alcazar of Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ. The green stars mark the hypothetical locations of the three figural sarcophagi. The orange stars signal the documented locations where non-figural sarcophagi were reused. Blue triangles indicate the previously documented placement of the marble basins. Finally, the red crosses show where statues were discovered. (Plan: Antonio Vallejo Triano, La ciudad califal de Madinat al-Zahrāʾ: Arqueología de su excavación [Cordoba, 2010], fig. 9 [reproduced with the author’s permission]).

Image courtesy of the Archaeological Site of Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ

Figure 5 Fragment of a head Image courtesy of the Archaeological Site of Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ

Furthermore, this female portrait is the only sculpture linked to literary sources. A tenth-century account reports that the southern gate of the city was referred to either as Bāb al-Ṣūra (the Statue Gate) or Bāb al-Madīna (the City Gate ).23Ibn Ḥayyān, MuqtabisVII, pp. 49 and 120, trans. Anales palatinos, pp. 68 and 153. Later, a female statue placed at gate, perhaps the same one, was eventually removed by the Almohad caliph in 1190 A.D. As stressed by Acién, the people of Córdoba considered the statue to be a talisman identified as Venus (Zuhara).24Ibn ʿIḏārī, Kitāb al-bayān, III, p. 14. See also Acién, “Materiales”, pp. 189-190; Elices, “Pagan statues”, p. 123. Together, these two literary accounts suggest that the visibility and legibility of ancient sculpture were criteria that underpinned the reuse and display of these pre-Islamic images in an Islamic context.

A long-established collection: from Damascus to Córdoba

⌅Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ was not the only place where ancient figurative sculpture was reused and displayed by the Umayyads. Literary and archaeological evidence reveals that ancient sarcophagi were reused at the Alcazar of Córdoba. A recent study by Márquez and Atenciano analyzed fragments of sarcophagi preserved in the Archaeological Museum of Córdoba, and they concluded that two sarcophagi would have been reused in the Alcazar during the Umayyad caliphate: a fragment depicting the triumph of Bacchus in India was displayed in the caliphal baths within the Umayyad palace; and, a fragment of a second Roman sarcophagus with a scene not identified probably belonged also to the Umayyad palace.25Inv. Nos. 24480 and 432. Marfil, “Los baños”, p. 60; Márquez and Atenciano, “Nuevos hallazgos”. I am most grateful to these scholars for providing me with these references.

It seems likely that the collection of antiquities that was reused at the Alcazar would have predated that of Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ26On this hypothesis see also Elices, “La escultura”, p. 111 and Antigüedad, pp. 71 and 348.. Literary sources report that ʿAbd al-Raḥmān II (r. 822-852) reused a marble basin as a water fountain, which he placed at the Gardens Gate, where it was visible to and used by the inhabitants of Córdoba.27Ibn Ḥayyān, MuqtabisII-I, p. 281, trans. Makkī and Corriente, Crónica de los emires, p. 172. Literary accounts also indicate that ʿAbd al-Raḥmān I brought several pre-Islamic and talismanic images depicting Arab conquerors to the Alcazar, and these are the very same images that the Visigothic King Rodericus (r. 710-711) discovered in Toledo; it is claimed Rodericus’s discovery of them broke an enchantment protecting his kingdom from the warriors they depicted.28Ibn ʿIḏārī, Bayān, II, p. 3. See also ElicesAntigüedad, pp. 47 and 71. Evidently, the reuse of these images was charged with significance. On the basis of these early references to the display of sculpture at the Alcazar, rather than Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ, it may be argued that the practice of spoliation was an Umayyad recurrent strategy for legitimizing and constructing an identity for their dynasty. Furthermore, this practice is documented as early as the emiral period, which opens up the possibility of connecting Umayyad practices in al-Andalus with examples of the reuse of sculpture in the mosques and palaces built in the Levant by the Umayyad’s ancestors. For example, the early Islamic “desert palaces” attributed to the Syrian Umayyads. Qaṣr al-Ḫayr al-Šarqī, Qaṣr al-Ḫayr al-Ġarbī, Kirbat al-Mafḫar, Quṣayr ʿAmra, and Mshatta were all decorated with ex novo sculptures.29Significantly, a head of a statuette representing Athena was discarded and reused as building material: Merker, “A statuette of Minerva”. Fragments of reused sculpture have also been discovered at the Umayyad bathhouse of Ḥammām al-Ṣarāḥ, and they may have formed part of a decorative fountain pool.30Bisheh, “Ḥammām al-Ṣarāḥ”, pp. 227-228, and pl. 63 a-d. Another literary account reports that ʿUmar II (r. 717-720) gathered a collection of Pharaonic statuettes at his palace in Damascus.31al-Maqrīzī, al-Ḫiṭaṭ, I, p. 110. Given the precedent set by these examples, the collection at Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ may have been intended as a visual commemoration and a dynastic assertion of Umayyad practices that had been established in the Levant, and was then subsequently replicated and developed in al-Andalus.

The multiple origins of a collection

⌅Literary sources also emphasize that the palace of Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ was adorned with columns and colored marbles gathered from a wide range of locations, including the Frankish kingdom, Rome, Carthage, Sfax. Two carved basins were among the most remarkable pieces: a large golden basin (ḥawḍ), which come from Constantinople, and a smaller green piece carved with human figures (wa-tamāṯīl ʿalā ṣuwar al-insān), that were originally from Syria. The literary sources also identify Tarragona, Málaga and Almeria as further sources for the marble used in Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ.32Ibn ʿIḏārī, Bayān, II, pp. 246-247; Ḏikr, p. 135 and transl. p. 173; al-Maqqarī, Nafḥ, I, pp. 526-527 and 568.

The literary accounts’ description of the origin of the marble and antiquities displayed in Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ are framed by a number of topoi. They echo reports that stressed the prestigious non-Islamic origin of columns, spoils, and idols which were reused or displayed in mosques or palaces at Damascus, Baghdad, or Samarra.33On the marble sources in Samarra: Milwright, “Fixtures and Fittings”, pp. 87 and 89. A basin transported and reused in Samarra: Brown, “The Cup of the Pharaoh”. Building material brought and reused in Umayyad mosques: Guidetti, In the Shadow, pp. 97-123. However, analysis carried out in Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ indicates that the materials used to build the city came from marble and limestone quarries located closer to Córdoba.34Vallejo, La ciudad califal, pp. 116-117. The literary accounts may be referring to with the dodecagonal basin place in the room adjacent to the Salon Rico (Fig. 3). As mentioned above, it seems to have been a pre-Islamic piece. Hernández and Castejón compared it to baptismal basins found in Jordan, Syria, and Palestine.35Hernández, Madinat al-Zahra, pp. 58-59; Castejón, Medina Azahara, p. 29. However, no archaeological evidence testifies to the sarcophagi being imported to al-Andalus during the Medieval period. Instead, Vallejo suggested that the basins found in Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ were retrieved from the Roman necropolis of Córdoba and other ancient Roman sites.36Vallejo, La ciudad califal, p. 116; Beltrán, Los sarcófagos, pp. 112 and 153. The statues may have been taken from the same locations.37Beltrán, “Hermeraclae”, p. 163. From at least as early as the late ninth century the outer limits of Cordoba had reached the western Roman necropolis. Fatwas issued around that period suggest that discoveries of pre-Islamic sculpture were commonplace, for example, the cadi of Córdoba, Ibn Lubāba (d. 314/926), indicated that building material retrieved from cemeteries could not be reused in mosques and bridges.38al-Wanšarīsī, al-Miʿyār al-muʿrib, VII, p. 103. See also Elices, “La reutilización”, pp. 7-9.

It is very likely that some sarcophagi and statues would have been brought from ancient sites other than Córdoba.39Beltrán, et al., Los sarcófagos, p. 40; Vallejo, La ciudad califal, p. 116; Calvo, “The Reuse”, p. 9; Elices, Antigüedad, p. 355. The spoliation of antiquities from Mérida that were reused at Córdoba is clearly demonstrated by both literary and archaeological evidence.40See the Arabic sources that comment on a Latin inscription discovered in Merida, as well as building materials brought to Córdoba and reused for the mosque: Elices, Antigüedad, pp. 77 and 127-132. Indeed, Vallejo has discussed how there are significant parallels between non-figural sarcophagi found in Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ and those retrieved from Mérida.41Caballero and Mateos, Visigodos y Omeyas, p. 454. On the sarcophagi discovered in Mérida, see Mateos, “Sarcófagos decorados”. A sarcophagus decorated with a scene of an aduentus — a Roman ceremonial reception — indicates this was a type of traditional manufacture undertaken by workshops in central Italy and Gallia.42Beltrán, et al., Los sarcófagos, p. 148. The statues may also have come from other sites besides the Roman necropolis of Corduba. Small or life-sized sculptures, particularly male and female portraits as well as statues of the gods, such as the herma of Hercules, in addition to the portraits documented at Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ, have been frequently identified in Late Antique collections of sculpture, which were displayed at thermae and villae.43Stirling, “Shifting Use”, p. 270. The statuary is often less than life-sized. Portraits and Pagan images of Venus or Hercules were popular: Beltrán, “Hermeraclae”, p. 167. The collections also include pieces of great quality. For an earlier discussion of this hypothesis, see Elices, “La escultura”, p. 110 and Antigüedad, p. 355, note 1357.

Literary sources also suggest that one criterion for the collection of antiquities reused at the Alcazar of Córdoba might have been the items’ diverse origins and heterogeneity. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān I is said to have brought several ancient talismanic images to the palace, which had been discovered in Toledo, as mentioned above.44Ibn ʿIḏārī, Bayān, II, p. 3. See also Elices, Antigüedad, pp. 47 and 71. Spoils from the sack of Narbonne were also transported and stored at the Alcazar in 177/793.45al-Maqqarī, Nafḥ, I, p. 464. In addition, ʿAbd al-Raḥmān II brought columns (al-ʿamud) and instruments (al-ālāt) to the Alcazar from all the regions of al-Andalus46Ibn Ḥayyān, Muqtabis II-1, p. 293, trans. Makkī & Corriente, Crónica de los emires, p. 172. I am not clear what “instruments” refer to, but.. The literary sources also indicate that the collection at the Umayyad Alcazar included Greek (al-Yūnānīn), Roman (al-Rūm) and Visigothic (al-Qūṭ) antiquities,47al-Maqqarī, Nafḥ, I, p. 464. and this suggests that the collection’s broad scope was planned, emphasized and probably acknowledged by the audience.

On the basis of the foregoing discussion, the collection of sculpture that was reused at Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ was not the result of a singular and unique discovery, but rather the methodical accumulation of meaningful pieces over time, and these were retrieved from a range of locations. By highlighting these antiquities’ diverse cultural and geographical origins, whether real or attributed, the literary sources shed further light on how these spolia played an active role in the construction of Umayyad legitimacy, memory and identity, understood as an accumulation of a rich combination of references.

Transcultural practices of collecting and the singularity of Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ

⌅The collection at Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ echoed multiple practices of reuse and it merged a range of cultural traditions. It may be argued that it was the very last Late Antique assemblage of sculpture on the basis that it continued the very same practices of recycling and reuse recorded in Late Antiquity. Furthermore, it engaged with the same aims, stressing the prestige, power, and education of the sculptures’ owner.48Stirling, “Shifting Use”, p. 270. The Umayyad collecting practices also echo Qurʾanic characters and Islamic traditions. Solomon is recorded as having had several statues and basins installed in a palace built by ǧinns (demons) who were subject to his authority.49Qurʾan, 34:12-13. Similar practices of spoliation were carried out by other Islamic rulers. In the “Ḥarim” of the Dār al-Ḫilāfa in Samarra, Herzfeld discovered a huge circular basin carved from a single piece of red-hued Egyptian granite. This singular piece, probably a Late Antique labra, was known as the “Cup of Pharaoh” (kāsat firʾūn) and it was reused as a water basin in the middle of the courtyard of the Great Mosque of Samarra.50Brown, “The Cup of the Pharaoh”. During the late ninth century Egypt, looters uncovered a sarcophagus and an alabaster stele, that had been broken in two. The stele was adorned with a depiction of three figures, and it was taken to the ruler, Aḥmad ibn Ṭūlūn, who ordered a craftsman to repair it. Later, two court secretaries re-signified the figures as Moses, Jesus and Muhammad.51Ibn Khurdādhbih, Kitāb al-masālik,pp. 159-160. In Alexandria, a sarcophagus of the Pharaoh Nectanebo II (360-343 BC) was reused as a water basin, displayed at the center of the al-ʿAṭṭārīn Mosque and reported to have belonged to Alexander the Great.52British Museum, EA10. See also Brown, “The Cup of the Pharaoh”, pp. 64-65. At Constantinople, Basil I (r. 867-886 AD) removed basins from the Hippodrome and displayed them in the atrium of his Nea Ekklesia, decorated with additional zoomorphic bronze sculptures.53Chronographia, pp. 277-279 and 297-299; Brown, “The Cup of the Pharaoh”, pp. 72-73. The basin probably evoked the description of Solomon’s brazen sea or throne, which was also associated with zoomorphic sculptures and automata.54On the image and throne of Solomon in Constantinople: Iafrate, The wandering throne, pp. 60-72.

The conjunction of the foregoing references suggests that a cultural strategy of reusing and displaying ancient basins and sculptures was pursued across the Mediterranean region, above all to forge associations with pre-Islamic kings and prophets. The aforementioned collection of Pharaonic statuettes displayed at the palace of ʿUmar II (r. 717-720) — a precedent for the collection displayed in Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ—, was also connected to episodes from pre-Islamic history: the statues were considered to be petrified men that God punished for following Pharaoh instead of Moses.55Qurʾan, 10:75-93; al-Maqrīzī, al-Ḫiṭaṭ, I, p. 110. Already mentioned in Elices, “La escultura”, p. 115 and Antigüedad, 353. For the Umayyads, collecting antiquities, relics, and spolia associated with pre-Islamic prophets and kings would have been particularly meaningful as a strategy of legitimation, as it enabled them to connect themselves with a long line of universal pre-Islamic kings and prophets who led to the Prophet Muhammad, whereby they could claim to be the pious and rightful leaders of the umma, and the heirs and protectors of Muhammad’s legacy and orthodoxy.56Rubin, “Prophets and caliphs”, pp. 98-99.

A potent political and religious narrative along these lines is documented in al-Andalus. ʿAbd al-Malik b. Ḥabīb (d. 853 CE), a senior legal advisor (mušāwar) to ʿAbd al-Raḥmān II and an influential figure on Islamic law and theology, wrote the first work of history to be written in Arabic in al-Andalus that has been conserved. His “Book of History” (Kitāb al-Taʾrīḫ) starts with the creation of the world and includes a history of the pre-Islamic prophets, focusing on the Prophet Muḥammadʼs mission, before continuing with a history of the caliphs and an account of the conquest of al-Andalus that includes a list of its governors.57Ibn Ḥabīb, Kitāb al-Taʾrīḫ. The collection at Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ would have most probably stressed the very same Umayyad strategy of constructing a sense of legitimacy and identity for the dynasty. Nevertheless, the collection is also a remarkable example of the early Islamic reception of classical sculpture, and it is unparalleled when compared with the Umayyad palaces in the Levant.58Elices, Antigüedad, pp. 345-346. The number of works, and their careful selection and display of sculpture signals that a new strategy was developed during the tenth century, one that sought to incorporate both non-Arab and Islamic references, while also foregrounding the specific context of al-Andalus.

In the early tenth century, Orosius’s Historiae Adversus Paganos was translated into Arabic, which provided the antiquities displayed in Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ with a deeper historical and cultural context and significance. The Arabic translation of Orosius was a transcultural enterprise carried out by a Christian judge and a Muslim Umayyad courtier.59Kitāb Hurūšiyūs, introd., pp. 28 and 33. A key focus was developed on the Iberian Peninsula in the work of Aḥmad al-Rāzī, who drew on the Arabic translation of Orosius, as well as other sources, including antiquities that could still be seen. Thereby, Aḥmad al-Rāzī was able to construct a narrative that stressed how the Umayyad’s power, conquests, and appropriations had founded a distinctive political and cultural identity in the Iberian Peninsula.60Crónica del Moro Rasis; Elices, Antigüedad, pp. 306-328. Therefore, the histories of a range of realms became entwined with Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ. The reuse and display of spolia enabled the Umayyads to both establish connections to and distinguish themselves from figures and episodes from the human and sacred history shared by Muslims, Christians and Jews throughout al-Andalus and the Mediterranean. Thus, it may be argued that the collection was underpinned by political, religious and cultural concerns spanning historical time and the Mediterranean region, all of which underscored the power and legitimacy of the Umayyad caliphs.

Antique Sculpture and Trans-culturalism in Islamic Context

⌅A number of literary sources provide polysemic insights into the antique sculpture displayed in an Islamic context. A brass female idol (ṣanam) was sent to Caliph al-Muʽtadid in 896 as part of the booty captured in India. It was first transported to Basra and Baghdad and then taken later to the caliphal palace, before finally being displayed in the prefecture of police (maǧlis al-šurṭa) for three days. The crowd that gathered there called it šuġl (the Distraction), a name conveying both fascination and a rejection of idolatry. Evidently, the statue conveyed an entwined transcultural, trans-regional, and trans-historical message associated with its origin and function, as well as its transfer to and display in Baghdad: it evoked both the Ǧāhiliyya and Islam, local and supralocal distant realms, as well as a range of cultural attitudes and political and religious responses towards sculpture.61al-Masʿūdī, Murūǧ, pp. 8 and 125-127; Flood, Objects of Translation, pp. 31-32. On the basis of this example, the final part of this study explores three approaches to the analysis of the sculptures displayed in Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ, and they address how these antiquities were displayed as transcultural, trans-regional and trans-historical devices.

A transcultural collection: Contexts, Practices, and Agents

⌅The sarcophagi and statues were displayed in Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ as part of a setting concerned with Umayyad representation and legitimation. Ancient sculpture, as figural representation, conveyed powerful messages in medieval Islamic societies.62Elices, “La reutilización”, pp. 9-14, “La escultura”, pp. 112-114 and Antigüedad, pp. 345-364. On the roles of figured antiquities in an Islamic context see Flood, “Image against Nature”; Elices, “Pagan Statues”; Mulder, Imagining Antiquity. Rather than being prohibited, their display was seemingly controlled or guided to ensure they were correctly identified by their spectators. The account of the female statue publicly displayed in Baghdad indicates that a protocol was used in conjunction with the careful staging of such displays. There are similar accounts of the display of ancient sculpture in Umayyad al-Andalus. A number of literary sources record how a female statue stood above Córdoba’s main gateway, the Gate of the Bridge or the Statue (Bāb al-Ṣūra). It was considered to be a talisman, and it was known as the “lady” (ṣāḥiba) and identified as a representation of Virgo.63Ibn ʿIḏārī, Bayān, III, pp. 13-15. See also Elices, “Pagan Statues”, pp. 119-121. A similar carefully planned setting may be identified for Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ. Literary sources also record a Bāb al-Ṣūra and point to a female statue considered to be a talisman identified as Venus.64Ibn Ḥayyān, Muqtabis VII, pp. 49 and 120, trans. Anales palatinos, pp. 68 and 153. Ibn ʿIḏārī, Kitāb al-bayān, III, p. 14. See also Acién, “Materiales”, pp. 189-190; Elices, “Pagan statues”, p. 123. However, the fragmented and decontextualized nature of the sarcophagi and statues identified in Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ, render it impossible to determine how each sculpture was integrated into the setting it was placed in. One can only venture hypotheses. Both sides of the Sarcophagus of Meleager depict arches and trees, which probably referred to an architectural setting, the palace of Oeneus. Yet, this decorative motif also linked the sarcophagus to the specific setting of the Court of Pillars and the arches and gardens at Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ.65Beltrán, Los sarcófagos, pp. 129 and 138. Antiquities could be integrated into the architectural settings in which they were displayed and also associated with other objects, figural motifs, and furnishings, such as curtains, wall hangings, epigraphic bands, or oil lamps.66On the role of decoration and architectural setting in Islamic palaces: Milwright, “Fixtures and Fittings”, pp. 105-108; Anderson, The Islamic Villa, pp. 72-97 and 135-155. Thereby, they helped convert Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ into a unique setting that caused bedazzlement (bahr) and astonishment (raw), and conveyed “the splendor of the monarchy (bahǧat al-mulk) and the majesty of power (faḫāmat al-sulṭān)”.67al-Maqqarī, Nafḥ, I, pp. 367 and 392-393.

The activities that took place in the palace’s interior and exterior spaces also helped shape the purpose and meaning of the antiquities displayed in Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ. Rather than solely being associated with science and learning, antiquities formed part of and added to the pomp of both formal public ceremonies, as well as the private gatherings and feasts held at the Umayyad court. Political and religious ceremonies along with triumphal military parades were held or led through the gates leading into Córdoba and Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ, beneath the female statues displayed upon them; for example, in 360/971 a parade was held to receive the Banū Ḫazar, new allies in the conflict against the Fatimids in North Africa, and in 362/973 another was staged to mark the celebration of the Breaking of the Fast.68Ibn Ḥayyān, Muqtabis VII, pp. 49 and 120, transl. Anales palatinos, pp. 68 and 153. Literary accounts also report that a ceremony was organized for the reception of a basin that had been brought from Constantinople, and which may have been none other than the circular dodecagonal basin that was placed in the room adjacent to the Salon Rico (Fig. 3); on receiving it, the caliph gave orders that twelve zoomorphic statues made of red gold were to be added to it, which would serve as water fountains. The statues were made in the caliphal workshops under the direct supervision of Prince al-Hakam. They may feasibly have been similar to the bronze sculptures of deer recovered from the city’s ruins, which were also used as water fountains.69Ibn ʿIḏārī, Bayān, II, pp. 246-247; Ḏikr, p. 135 and transl. p. 173; al-Maqqarī, Nafḥ, I, pp. 526-527 and 568. At least three zoomorphic deer had been associated with Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ: Doha Museum, MW.7.1997; Museo Arqueológico de Córdoba, CE000500 and MAN, no. 1943/41/1. The meaning of other sarcophagi and statues displayed in the city’s courtyards would have been restricted to private contexts. Feasts, musical performances, and poetry recitals enabled the caliphs to forge ties with the members of the Córdoban elite and legitimize their rule. To celebrate the construction of an aqueduct ʿAbd al-Raḥmān III held a feast at the munya Dār al-Nawūra, where thanks to this feat of engineering water gushed from the mouth of a marble lion.70al-Maqqarī, Nafḥ, I, pp. 564-565. On the ceremonies and feastings held at the Umayyad court, see Anderson, The Islamic Villa, pp. 137-144, and particularly Manzano, La corte, pp. 269-295. Given the importance of activities like hunting and feasting as part of the social life of the Umayyad court, the Pagan images that adorned sarcophagi and statues lent themselves to an interpretation closely linked to the refined elite culture of the court. The scenes depicted upon the sarcophagi echoed the activities of the caliph and his court engaged in: the sculpture depictes hunts, parades or aduentus, bucolic scenes, ceremonies and performances with male and female characters holding literary works, wearing cloaks or playing the aulós —an ancient wind instrument— (Fig 6).

Image by the author with permission of the Archaeological Site of Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ.

Figure 6 Fragment of a sarcophagus depicting a female figure playing the aulós. Image by the author with permission of the Archaeological Site of Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ.

Finally, poets, astrologers, chroniclers, and court secretaries were the target audience of the messages embodied by the ancient sculpture, and they also played a key role in decoding or re-signifying the antiquities, as well as stressing the transcultural and polysemic nature of the collection. This educated elite was well versed in poetic and astrological imagery, as well as Qurʾanic traditions and non-Arabic sources. While it is unclear whether the depiction of Hercules in the figural sculpture displayed at Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ was identified as an ancient king and conqueror of Iberia, as is mentioned in the classical sources translated in the tenth century; however, it is apparent that pagan sculpture was re-signified in a number of ways.71Elices, Antigüedad, pp. 351-353. It seems likely that both poets and astrologers would have been responsible for this task.

Rosser-Owen, has discussed how during the Amirid period, the marble figural basins that were made for and displayed in Madīnat al-Zāhira were viewed by the court poets and panegyrists as “poems in stone”.72Rosser-Owen, “Poems in Stone”. Hercules, Alexander/ Ḏū l-Qarnayn and Solomon were also invoked in poems as comparisons for ʿAbd al-Raḥmān III and al-Manṣūr.73Ibn Ḥayyān, MuqtabisV, p. 62, transl., Crónica del califa, pp. 57-58; al-Maqqarī, Nafḥ, III, p. 189. Astrologers at the court also identified the female statue that stood on the Bab al-Ṣūrain Córdoba as a talisman depicting Virgo, and it was most probably they who identify the aforementioned female statue in Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ as Venus.74Elices, “Pagan Statues”, pp. 131-132. Aḥmad al-Yūnānī (the Greek) al-Faylasūf (the Philosopher) and Bishop Rabí or Recemundus, were all mentioned in connection with the two basins brought from Syria and Constantinople. They were most probably responsible for transporting them to al-Andalus, as well as selecting the pieces and identifying their value, meaning, and “life histories”. According to Fierro, this is one of the first appearances of the term “philosopher” in Andalusi texts and she suggests it refers to a Byzantine individual.75Fierro, La heterodoxia, p. 162, note 4. Significantly, the term is also found in Byzantine literary sources, the Parastaseis and the Patria, to point to the individuals capable of identifying and conveying the meaning of the ancient sculptures that were displayed in Constantinople.76Parastaseis, pp. 14, 37, 64, 75 and 80; Patria, III, 34 and IV, p. 19. Thus, Aḥmad al-Yūnānī and the bishop Rabī were transcultural agents, capable of relocating and re-signifying objects with a transcultural significance. They are very likely to have played a role in shaping the meaning of the sarcophagi and statues displayed in Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ, whereby the caliph’s collection was able to address a diverse multicultural audience.

A trans-regional collection

⌅Whether retrieved from the ancient cemeteries of Córdoba, from other pre-Islamic cities and settlements in al-Andalus, or, as the literary sources claimed, from other locations across the Mediterranean — the Frankish kingdom, Rome, Carthage, Sfax, Constantinople, Syria, the diverse sources of the antiquities gathered at Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ were very probably explicitly acknowledged. Thus, any analysis of this collection must consider not just the local context and its multicultural scope and dynamic, but also a far broader supralocal realm, encompassing both past and contemporary practices of spoliation in the Levant, the rivalry with both the Fatimid caliphate in North Africa and the Christian Iberian kingdoms, cultural and economic connections with Egypt, and also the role played by Italian and Byzantine diplomatic and trade exchanges.77Manzano, La corte, pp. 67-77, 186-190 and 210-224 delves into the political, religious, economic and diplomatic interests of the Umayyad caliphal administration throughout al-Andalus and the Mediterranean. In this regard it should be noted that the literary accounts stress the transcultural nature of the collection, and how it mediated the relationship between cultures, territories and rulers in order to underscore the authority and power of ʿAbd al-Raḥmān III as both caliph and the owner of such a remarkable collection of antiquities.78Vallejo, La ciudad califal, pp. 116-117; Elices, Antigüedad, pp. 354-356. This seems to have been one of the aims of this decorative program:

There was no one, absolutely no one, who entered the Alcazar [of Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ], even those from the most distant countries and diverse confessions, whether king, emissary or merchant [...] who could not categorically conclude that they had never seen anything like it, nor had they even heard of such a thing, nor had it ever occurred to them.79al-Maqqarī, Nafḥ, I, p. 566. See also Elices, “La escultura”, pp. 113-114 and Antigüedad, p. 356.

The collection of sculpture at Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ conveyed the intricate political, cultural and economic dimensions of the power wielded by the Umayyads caliphs during the tenth century.

A trans-historical collection: Past, Present, and Future

⌅Assemblages of spolia, relics, and ancient objects also served as an instrument of knowledge. By forming a collection of antiquities, it was also possible to organize a perception of the world and construct notions of time and history. One of the aforementioned literary accounts reports that the collection of antiquities at the Alcazar of Córdoba included a collection of Greek (al-Yūnānīn), Roman (al-Rūm) and Visigoth (al-Qūṭ) antiquities,80al-Maqqarī, Nafḥ, I, p. 464. and this reveals how historical, ethnic and artistic criteria underpinned the organization of this Umayyad collection. Furthermore, it may be argued that the sarcophagi and statues at Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ were intended not just as a reference to Classical Antiquity, nor merely the Past, but also to the Present and Future of al-Andalus and the Umayyad dynasty.

The reference to the Past is clear. Literary sources record how ancient remnants were associated with Hercules, Abraham, Pharaoh, Moses, Solomon and Alexander/Ḏū l-Qarnayn. Thus, it is probable that the antiquities displayed at Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ would have been perceived as traces (atār) or ʿaǧāʾib (wonder) and associated with these Qurʾanic or ancient figures.81Elices, “La escultura”, pp. 126-133, and “Pagan Statues”, pp. 130-133. The connection between the sarcophagi and zoomorphic bronzes displayed in Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ, and used as water fountains sheds further light on this perspective. Their display may have echoed a literary tradition attested since the ninth century: ʿAbd al-Muṭṭalib’s discovery of several objects in the sanctuary of Mecca, including two golden gazelles.82Shalem, “Made for the Show”, pp. 270-272. The figure of Solomon also played a significant role at Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ, whereby, the twelve zoomorphic water fountains that were added to the basin brought from the Levant might also have been intended as an allusion to the description of Solomon’s brazen sea or throne; although this was mainly associated with lions, all kinds of other animals and birds were also linked to it.83Bargebuhr, The Alhambra, pp. 120-140; Soucek, “Solomon's Throne”.

The antique sculptures at Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ were also linked to the Present, as tools of the Umayyad discourse of legitimation and representation. Considered as talismans, statues played meaningful roles for the whole community, as was the case for the female image placed at the main gate of Córdoba: it was considered to be the “lady” (ṣāḥiba) and protector of the city. The female statue that stood upon the main gate of Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ, was also considered to be a talisman identified with Venus (Zuhara). Both statues also conveyed political and religious connotations concerning the Umayyad’s rivalry with the Fatimids, who identified themselves with Fāṭima, the Prophet’s daughter, also known as al-Zahrāʾ.84Acién, “Materiales”, pp. 189-190; Fierro, “Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ”, pp. 316-322; Elices, “Pagan statues”, pp. 132-133.

The link between statues and astrology also signals how antique sculpture played a key role in conveying messages and lessons concerning future. Literary sources report how ancient antique sculpture was a repository of information that, if correctly interpreted, could prove useful and valuable. Statues therefore came to be associated with historical events, which astrologers had to predict. The two statues displayed on the gates of Córdoba and Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ were both linked with major political and historical events, in particular the downfall of the Umayyad caliphate and the outbreak of the civil war in al-Andalus.85Elices, “pagan statues”, pp. 120-121 and 123. Ancient sculptures were also connected to prophecies in Constantinople: Parastaseis, pp. 8, 20, 74. The aforementioned collection of statuettes displayed in the palace of ʿUmar II may also have been beheld in terms of apocalyptic and messianic messages that resonated amidst the contemporary religious and political context.86Qurʾan, 10:75-93; al-Maqrīzī, al-Ḫiṭaṭ, I, p. 110. Apocalyptic predictions about the imminent arrival of Judgment Day also figure prominently in the “Book of History” written by ʿAbd al-Malik b. Ḥabīb,87Ibn Ḥabīb, Kitāb al-Taʼrīḫ, introd. Aguadé, pp. 74-75, 87-100. and these prophesies may also have informed the spectacle staged with these sculptures in Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ.88Fierro, “Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ”; Elices, Antigüedad, pp. 182-190. For example, another literary account refers to the basins (ḥiyāḍ) and “wonderful statues of human figures (tamāṯīlʿaǧībat al-ašḫāṣ),” and then continues by stating:

Praised be He Who has empowered this weak creature [the human being] to create and invent all that with fragments of this earth doomed to decay, to make the servants who ignore Him see an example of what He has arranged for the blessed ones in the hereafter, where death does not exist, nor is there any need for restoration (ramm). There is no God, but God. He, incomparable in generosity.89al-Maqqarī, Nafḥ, I, p. 566.

The reference to the hereafter underscores the specific eschatological reading of the sculptures. Furthermore, the sarcophagi’s funerary and pre-Islamic origin and the fact that marble was a material capable of resisting time would have lent further weight to this eschatological significance, and also reinforced the trans-historical messages these antiquities conveyed regarding with regard to the past, present and future.90Elices, “La escultura”, p. 116 and Antigüedad, pp. 188 and 353-354. On the notion and perception of time with regarding to the material realm: Shalem, “Resisting time” and “Made for the Show”, 272 indicating that: “the objects’ recovery was understood as a sign indicating the beginning of a new era, as if the objects are waiting like souls for their “Resurrection Day” — the proper time to be reused by humankind”. Therefore, antiquities, as spolia from the past, went on to become a form of authentication for the passage of time and they are likely to have been perceived as devices for envisioning and encountering the sacred and eternity. Finally, through their associations to the caliph and courtly ceremonial, antiquities also conveyed the immobility, endurance and universalism of the caliphs' power.

Concluding remarks

⌅The collection of Roman sarcophagi and statues that were reused at Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ formed part of the Umayyad strategy of political and religious legitimation. Antiquity was deemed significant not only because ancient figures such as Hercules could be identified and linked with pre-Islamic sources and the history of al-Andalus, but above all because the Umayyads managed to transform and adapt ancient remnants from the Ǧāhiliyya into wider meaningful references that would be intelligible to a broader audience, while also being capable of alluding to multiple cultures, times and spaces simultaneously. The display of antiquities reified and recalled idolatry and its demise, articulated dynastic claims, while explaining political and religious changes over the course of history. Their role was by no means merely decorative, but rather social and didactic, and they functioned in various ways, often simultaneously, as objects or devices to be interacted with or learned from. Likewise, they were images that prompted fascination and repudiation, and they were also capable of playing a mediating role in the construction of legitimacy, identity, and memory.

Over the course of this article, I have demonstrated the transcultural dimensions of the collection of Roman sarcophagi and statues displayed in Madīnat al-Zahrāʾ. It was a miscellaneous collection, acknowledged and valued for that, comprising pieces with a wide range of characteristics, chronologies, and origins. The collection was a Umayyad creation, and was intended to be hybrid, eclectic, and ambiguous, and to convey transcultural, trans-regional, and trans-historical messages. The antiquities acquired their significance within a context of courtly culture and ceremonies, and their meaning would have been conveyed by poets, astrologers and chroniclers, who were responsible for re-signifying images from the past by invoking a whole range of cultural, temporal and spatial interconnections based on both pre-Islamic and Islamic literary traditions. The caliph’s collection succeeded in addressing a multicultural audience, blurring cultural and religious barriers, and bringing together the levant and al-Andalus, as well as Past, Present, and Future. Sarcophagi and statues conveyed a powerful ideological discourse that focused not merely on the legacy of Antiquity, but on the whole history of the world, while inserting the Umayyads into this narrative; God's creation was reaffirmed and the universal and diverse facets of the caliphs' power was celebrated.